OPINION:

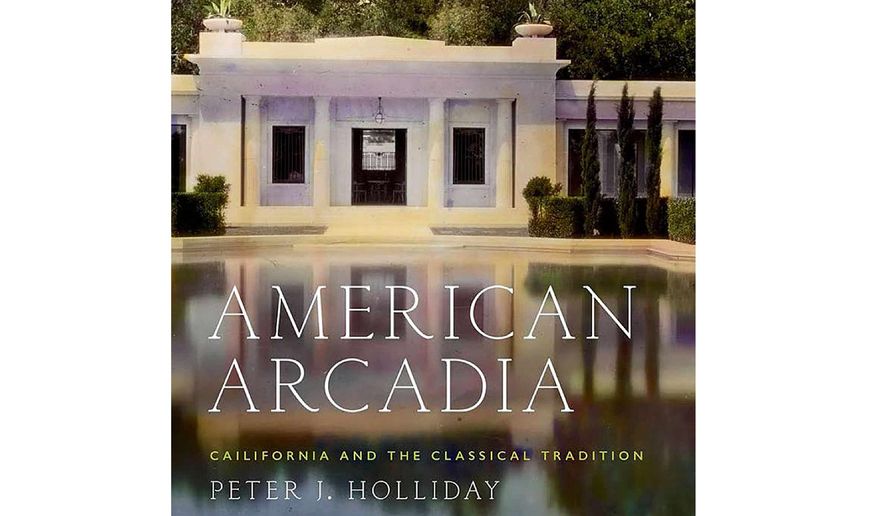

AMERICAN ARCADIA: CALIFORNIA AND THE CLASSICAL TRADITION

By Peter J. Holliday

Oxford University Press, $45, 446 pages, illustrated

Classic movie sets apart, California, that byword for the cutting-edge trendsetting contemporary in so many spheres, and the world of ancient Greece and the Roman Empire would seem to have little in common. Indeed, even Peter Holliday, a professor at California State University, Long Beach, the author of this handsomely illustrated and densely texted book, admits their surface incongruity:

“For somebody trained as a historian of classical art and architecture to write about modern California might, at first glance, seem a stretch.”

But he also sees similarities between how those long-ago cultures themselves evolved and the development of his home state:

“The phenomena of artistic assimilation and appropriation and the processes of self-fashioning I studied in classical antiquity parallel remarkably what I explore here.”

Mr. Holliday grew up in Southern California and has witnessed that evolution firsthand. Furthermore, he has done so with a natural eye, informed by deep familial roots, in addition to his acquired learning and erudition. The aspects of the state illuminated by his agronomist father’s and downtown Los Angeles businessman stepfather’s experiences and worldviews — to say nothing of his Santa Barbara grandparents and their olive- and citrus-dominated neighborhood — have all contributed to his extensive and profound attunement to his surroundings.

But for many of us who also actually live here, whether native Californians or those who, like myself, beheld its wonders first as a newcomer and now for more than 40 years, the connection doesn’t seem so strange. It’s not just the Mediterranean climate and vegetation which are so similar: There really are more than a few touches reminiscent of “the glory that was Greece and the grandeur that was Rome,” to use the immortal words of Edgar Allan Poe. Perhaps the most famous example is the Roman Villa J. Paul Getty created to house his art collection in Malibu, more readily associated with bikinis then with togas worn by Roman emperors like Hadrian. As Mr. Holliday shows us, such classical echoes are scattered far and wide.

Little more than a couple of hundred yards from where I am writing this review lies that bastion of hard science, the California Institute of Technology, not one might think the kind of place to boast obvious links with the humanistic past. Yet, as one who walks daily past them, I can attest to the accuracy of Mr. Holliday’s description of the campus’ older buildings: “Mediterranean allusion the Italianate Faculty Club, the Athenaeum (1931), and Hispano-Italian Romanesque dormitories, clustered around three courtyards.” He correctly observes that “Unfortunately, the modern buildings added after World War II tend to detract from the strong character of the original campus plan and its architecture.” But even in some of these, his probing mind can see classical echoes. I have walked past architect Edward Durrell Stone’s super-modernistic round white Beckman Auditorium thousands of times, but would never have thought of it as “a modern interpretation of a circular Roman temple.” Yet anyone looking at the illustration he provides can see that it does indeed “evoke a massive Temple of Vesta on the Caltech Campus” and I shall never look at the familiar edifice the same way again.

Mr. Holliday has a positive genius for linking even icons of modernity with the classical past. A case in point is his perceptive discussion of expatriate British artist David Hockney’s signature portraits centered on Los Angeles’ swimming pools, which, he points out, although “clearly set in contemporary California nevertheless evoke the classical pastorale.” He quotes another critic Christopher Knight observing that “Hockney’s pictures of swimming pools are contemporary adaptations of the conventional literary and artistic themes of the Golden Age. The voluptuous and sybaritic bather is a primary symbol of that classical myth of origin, a myth that speaks of a lost, pastoral Arcadia of peace and harmony, which stands in sharp contrast to the convulsively animated world of history.” Mr. Holliday then goes on to write that “the places his bodies occupy are erotically charged, which is not unprecedented since ancient pastoral poetry included romantic episodes.”

Putting modernistic masterpieces in such informed context is invaluable both in understanding them as works of art and the tradition in which they were painted. And after all, come to that, few things were as integral to Roman life as pools, whether for cleanliness or enjoyment.

Those bathing beauties so associated with California beaches and swimming pools, immortalized in generation after generation of movies and advertisements, are, Mr. Holliday reminds us, grounded in ancient world:

“Today the classical body is ubiquitous, for Greek and Roman art supplied the model for modern attempts to fashion and fathom the human body . The female ideal is a direct descendent of the Venus type and may constitute one of the more continuous instances of how subtly classical ideals affected the development of California culture; indeed, the ’California body’ may even be the longest lasting export of California culture to the rest of America.”

It is ingenious and surprising connections like this which make this not merely an instructive work but a thought-provoking and enjoyable one.

• Martin Rubin is a writer and critic in Pasadena, California.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.