OPINION:

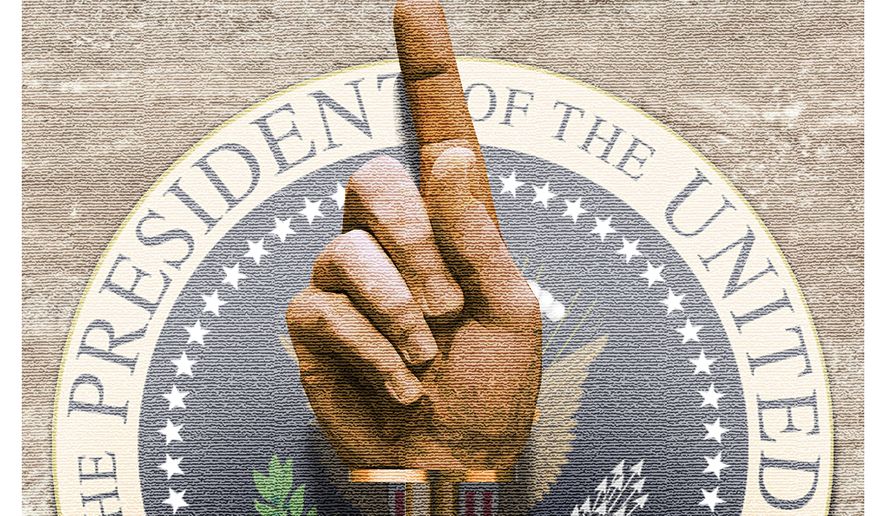

Critics of President Trump are once again attacking not just the man but also the presidency itself.

Opponents of his pardons and of the Supreme Court’s decision in Trump v. United States, the landmark presidential immunity case, reprise familiar but weak and anti-constitutional arguments aimed at this president but which would ultimately undermine the office of the president.

Citing pardons with which they disagree, Democrats invoke “checks and balances” as justification for reining in the president’s clemency power. Yet the pardon power is itself an executive branch check on the judiciary. It allows a nationally elected official to temper the judgments of a democratically unaccountable branch.

If Congress believes a president is abusing this power illegally, then the Constitution already provides a remedy. If voters disagree with presidential actions or congressional reactions, then they can render judgment at the ballot box. Sufficient checks and balances already exist; amending the Constitution to weaken the pardon power would be a mistake.

Article II grants the president authority to pardon offenses against the United States, except in cases of impeachment. The framers included this exception based on historical abuses, most notably King Charles II’s attempt to pardon Thomas Osborne, the earl of Danby, to shield him from parliamentary accountability.

The Constitution also forbids prospective pardons. A president cannot immunize someone in advance for crimes not yet committed.

Unable to challenge the power directly, Democrats in Congress are now taking aim at the process, seeking to expose internal deliberations and signaling plans to haul presidential aides before Congress should they regain control in the midterms. This is not constitutional oversight; it is an attempt to intimidate a coequal branch of government.

In Trump v. United States, the Supreme Court held that presidents enjoy absolute immunity from prosecution for core official acts. The pardon power plainly qualifies. The court further held that evidence of deliberations surrounding such acts is inadmissible and beyond the reach of investigators.

The rationale was straightforward: Executive privilege — a cornerstone of the republic since George Washington — would collapse if rival branches could rummage through internal deliberations whenever they disapproved of an official act. As Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. warned, such a regime would invite the executive branch to cannibalize itself, with each administration prosecuting its predecessor.

Critics point to two historical examples of congressional scrutiny of pardons. The first involves President Ford’s pardon of Richard Nixon, but Ford voluntarily testified before a House subcommittee. The second concerns President Clinton’s pardon of fugitive financier Marc Rich. Mr. Clinton himself did not testify, though he permitted aides to do so.

Neither episode weakens the court’s reasoning. Executive privilege, like attorney-client or doctor-patient privilege, belongs to its holder and may be waived. Ford’s choice to testify does not obligate future presidents to do the same, nor does Mr. Clinton’s decision regarding his aides create a binding precedent. The existence of a privilege is not undermined by the option to waive it.

Some critics speculate about “quid pro quo” pardons. The Constitution clearly identifies bribery as an impeachable offense, but quid pro quos are not inherently unlawful. Legislators engage in political bargaining routinely; one senator may support another senator’s legislation in exchange for the other senator’s vote to confirm a nominee.

Courts have recognized this distinction: the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals reversed several counts of former Illinois Gov. Rod Blagojevich’s conviction on the ground that public acts exchanged for other public acts do not constitute crimes. If Ford had agreed to pardon Nixon in exchange for Nixon’s resignation, sparing the country a prolonged impeachment, then such an arrangement would have been not only lawful but also commendable.

Others complain that Mr. Trump has disregarded Justice Department guidelines for clemency. These criticisms echo those of former pardon attorney Liz Oyer, who invokes both the “letter” and “spirit” of internal guidance. Some even ask whether the State Department approved a particular pardon.

Still, Article II is unambiguous: “The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.” Not the Justice Department. Not the State Department. Not unelected bureaucrats. The president and the president alone decides who receives pardons or commutations. Congress has no authority to conduct fishing expeditions disguised as oversight simply because it dislikes a clemency decision.

If Democrats retake either chamber of Congress this year, then they will almost certainly unleash a flood of subpoenas under the banner of oversight. Many will attempt to unlawfully intrude upon executive privilege. Pardons will be a prime target, and the administration must resist these incursions at every legal turn.

As Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh observed in the immunity case, this debate is about more than any single president. It is about the presidency itself. The president, Congress and the Supreme Court must remain steadfast against efforts to weaken a constitutional office simply because of disdain for the current officeholder.

• Michael Zona is a partner at Bullpen Strategy Group and a former communications director for Sen. Charles E. Grassley of Iowa.

Correction: A previous version of this column stated the incorrect year for the 2026 midterm elections.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.