OPINION:

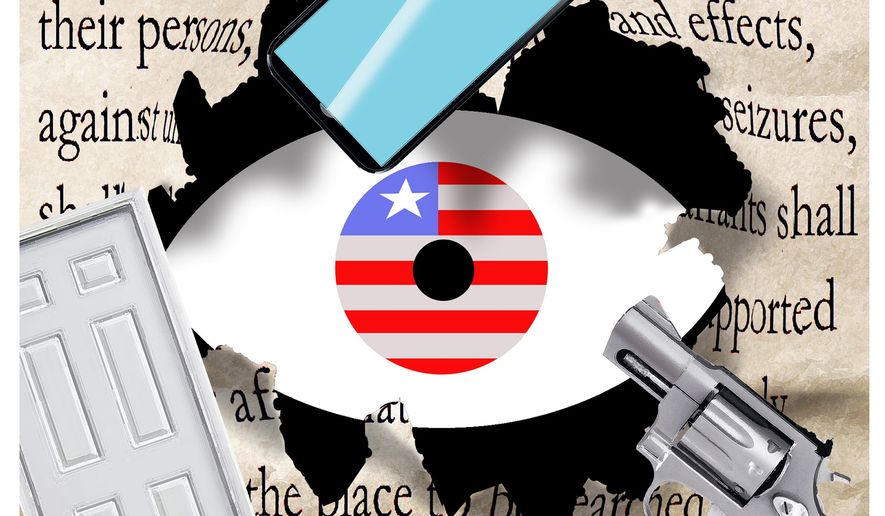

“The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects against unreasonable searches and seizures shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.” — Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution

Last week, in an unsigned order issued without an explanation, and in direct defiance of the plain language of the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution, the Supreme Court of the United States permitted federal police to stop people in public and demand to see proof of lawful presence here, and in the absence of that proof, to arrest them.

Here is the backstory.

In 1765, when the British king and Parliament were looking for creative ways to tax the Colonists in America, Parliament enacted the Stamp Act. This law required the Colonists to affix British stamps, purchased from British agents in America, to all papers in one’s possession in one’s home. The stamps were required on all legal, financial and personal documents; on every book, newspaper and pamphlet; even on broadsides or posters intended to be displayed publicly.

The stated purpose of the act was to generate revenue to fund British soldiers for security in the Colonies. The act was enforced by the execution of writs of assistance.

In 1765, British agents began to execute these writs of assistance in America. The writs were search warrants that did not describe the place to be searched or the person or things to be seized, but rather authorized the bearer to search wherever he wished and seize whatever he found. A secret court in London issued these general warrants upon a showing only of governmental need. Such a showing was, of course, meaningless because whatever the government wanted, it would tell the court it needed.

When some students at the College of New Jersey, now Princeton University, calculated that the Stamp Act cost more to enforce than it generated in revenue, many Colonists realized that this dreadful law was only secondarily a revenue generator. Its true but unstated purpose was to enable the king, through his agents, to enter Colonial homes on the pretext of looking for stamps but truly looking for revolutionary materials.

The Colonial reaction was so ferocious toward the British sellers of stamps and the agents executing the general warrants that Parliament rescinded the Stamp Act in 1766. Still, the die had been cast.

After the revolution was won and the Constitution ratified, the 13 states ratified the first 10 amendments to the Constitution: the Bill of Rights. The theory of the Bill of Rights is not that the new government would grant rights, but rather that it was prohibited absolutely by legislation or executive decree from interfering with rights.

From where did the framers believe that human rights came? According to the Declaration of Independence and codified in the Ninth Amendment, from our humanity, as a gift from the Creator.

The Fourth Amendment is the most radical of the first 10. It recognizes that personal privacy — the right to be left alone — is a natural right, and the government may interfere with it only upon obtaining a warrant from a judge based on probable cause of crime about the person or place named in the warrant, a warrant that specifically describes the place to be searched or the person or things to be seized.

Because privacy is a natural right, when it is challenged, no person needs to prove or disprove anything by showing papers. The burden of substantiating the challenge to privacy is 100% with the government.

Now, back to the Supreme Court’s decision in its shadow docket.

The shadow docket, a creation of the court under Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., is deeply frustrating and profoundly disturbing to the judicial, academic, legal and law enforcement communities as it often produces orders without reasons. Stop/go. Yes/no. We’ll tell you why and how at a later date.

That was what happened in a challenge to mass arrests by Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents in Los Angeles this summer. People arrested without arrest warrants — arrested collectively because of the colors of their skin, the sounds of their voices, the places of their lawful assemblies — challenged their arrests. A federal district court judge invalidated the arrests and ordered ICE to follow the requirements of the Fourth Amendment. A federal appellate court upheld the order.

Last week, in one of its stop/go, yes/no rulings, the Supreme Court reversed the two lower courts without giving reasons. In an irrelevant and embarrassing concurrence, Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh opined that if you are lawfully in the U.S., you have nothing to fear; just show your papers.

Show your papers!? That requirement undermines the truism that our rights are natural. It shifts the government’s burden when interfering with free movement from the government’s ability to demonstrate criminality to the stopped person’s ability to disprove it on the spot. As President Reagan once commented, such a command is the hallmark of totalitarian regimes.

These are dark days in America. A popular young man is publicly killed on national media because of his articulate expression of his political views. Two state legislators are killed in the middle of the night in their homes by a madman pretending to be a cop. The president kills unknown and unnamed strangers on the high seas and claims the power to kill dangerous people he thinks might commit crimes.

And now this: The Supreme Court, for the first time in the modern era, lets police demand to see your papers.

To my colleagues in media, law and academia who love liberty, WHERE IS YOUR OUTRAGE before you are stopped and have no papers to show?

• To learn more about Judge Andrew Napolitano, visit https://JudgeNap.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.