OPINION:

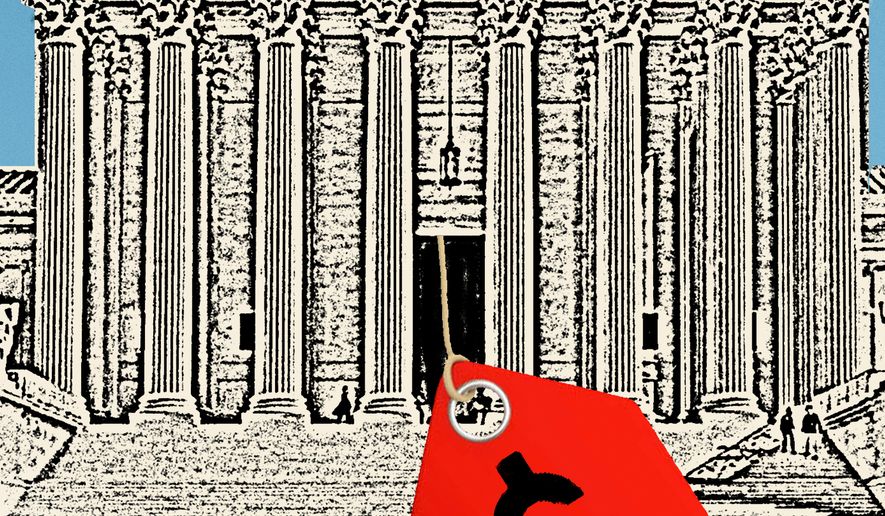

This week, the Supreme Court will begin the process of deciding whether the president can impose a sales tax on products and services originating in foreign countries and purchased in the United States. The president calls these taxes tariffs.

Tariffs are nearly as old as the republic. When imposed by Congress, as they have been going back to the presidency of Thomas Jefferson, they are clearly constitutional. Yet the questions before the court ask whether Congress delegated to the president the power to tax, and if it did, whether that delegation was constitutional.

The Justice Department argues that both those questions should be answered in the affirmative. However, if the court concludes that Congress never gave its taxing powers to the president, then it needn’t reach the second question. It should answer both questions in the negative, as there is simply no statute that Congress has authorized the president to impose tariffs on his own. Under the Constitution, only Congress may impose taxes.

The Justice Department argues that the National Emergencies Act of 1976 and the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 permit the president to address emergencies, and one of the tools for addressing these emergencies is the imposition of tariffs. Does the United States currently have an economic emergency? The president says the trade imbalance — American industry and consumers buying more from foreigners than foreigners buy from American industry — is somehow an emergency. It is not. We have had an imbalance of trade since 1934. Moreover, neither of the statutes upon which the president relies for authority to impose tariffs even mentions tariffs by name or implication.

The imbalance of trade is not an emergency under federal law. It has existed continuously since the Great Depression, and federal law defines an emergency as a sudden and unexpected event, such as a surprise military attack or a hurricane, that adversely affects the national economy.

If you use up your line of credit on one of your credit cards and you owe more than you currently have in your checking account, that is the functional equivalent of a personal imbalance of trade. Is that the fault of the folks from whom you purchased your goods? Should they be punished or taxed for selling you what you want to buy? Of course not.

Clearly, a state of affairs that has existed for 90 years is not sudden or unexpected. It is also a matter of basic economics that owing more than you have on hand is not the fault of the folks to whom you owe it. Nor is it necessarily a bad thing or one that begs for government remediation.

It is historically accurate that tariffs have been and can be used in economic emergencies; however, they must be authorized by Congress. The very first power delegated by the Constitution to Congress is the power to tax. Because Congress has given the president the power to address emergencies, he has assumed that among these powers is the authority to tax. Still, taxation is a core function of Congress — meaning it is expressly granted to Congress in the Constitution — and we know from Supreme Court jurisprudence that core functions cannot be delegated away.

Congress can no more delegate to the president the power to tax than it can the power to prescribe punishments for federal crimes. The president can no more exercise the taxing power than he can delegate to the chief justice the power to be the commander in chief of the armed forces.

These powers — Congress enacts federal laws and declares war, the president enforces the laws Congress has enacted and wages war, the courts interpret the rules and the Constitution — are intentionally and uniquely circumscribed and precisely assigned to each of the three branches. This circumscription and these assignments are collectively referred to as the separation of powers.

Powers in the federal government are separated not to enhance the hegemony of each branch but to prevent the accumulation of excessive power in one branch at the expense of either of the other two branches, thereby diminishing their ability to check the branch that has excessive power, thus threatening personal liberty.

Stated differently, James Madison, the scrivener of the Constitution, intentionally crafted “jealousy” — his word — between and among the branches. He intended that jealousy would serve as a check on the accumulation of too much power in one of the branches. His goal was the maintenance of limited government, thereby assuring maximum personal freedom.

An example of this is war. Under the Constitution, only Congress can declare war and only the president can wage war. If Congress were to delegate away to the president — or if the president were to seize from Congress while it slept — the power to declare war, then he would enjoy the power to declare and to wage war. That would make him akin to British monarchs before the ascendancy of Parliament, an evil Madison sought mightily to prevent.

Where does all this leave us?

In a democracy, the people are entitled to expect that the individuals they have elected will adhere to the Constitution, but presidents and Congress have continually sought to expand their powers beyond the limits of the Constitution.

Madison understood that government is the negation of liberty, and thus its powers must be carefully circumscribed. Yet, when government — here, the president — does something that is clearly beyond his constitutional authority and affects us all, it is the duty of the courts to correct him.

The whole purpose of an unelected life-tenured judiciary is to be anti-democratic, to restrain the unlawful impulses and extra-constitutional behavior of the popular branches of government. If any time ever called for that restraint, it is now.

• To learn more about Judge Andrew Napolitano, visit https://JudgeNap.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.