OPINION:

As the Trump-Vance administration shapes up and selects its Cabinet and advisers, the looming Senate confirmation process, which may prove challenging for certain picks, raises the possibility of recess appointments.

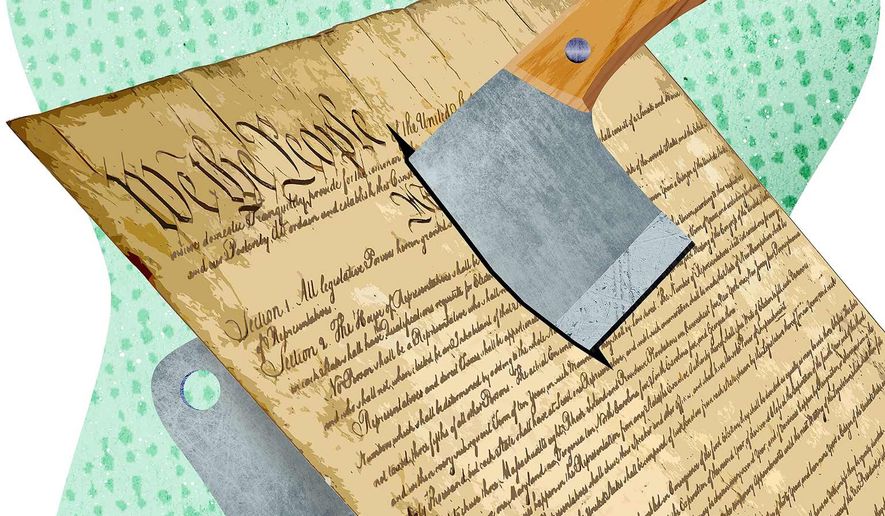

The Constitution provides a structural safeguard for the fulfillment of executive offices by requiring high officials to discuss and agree upon the caliber of appointee that may fill an office. For cases when delays are inevitable and problematic, the founders created the recess appointments clause — which was designed to be the exception, not the rule.

The Constitution’s recess appointments clause allows the president to bypass the Senate and confirm a Cabinet pick in an emergency. While recess appointments aren’t new and have been used (or abused) by most modern presidents to quickly confirm positions that require Senate approval, they should never be the default in confirming candidates to quicken the process and avoid Senate deliberation.

The advice and consent of the Senate, though not explicitly stated as such, is essentially grounded in Scripture because, as Proverbs 11:14 says, “In the multitude of counselors there is safety.”

As with any question involving the meaning of a constitutional provision, one must start with the relevant text. The appointments clause of Article 2, Section 2 states the president “shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the Supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not herein otherwise provided for, and which shall be established by Law: but the Congress may by Law vest the Appointment of such inferior Officers, as they think proper, in the President alone, in the Courts of Law, or in the Heads of Departments.”

In layman’s terms, the president can nominate officers of the United States but must first receive the advice and consent of the Senate before they can take office.

While that seems simple enough, problems can arise when the Senate is not in session and thus cannot fill an important position. The founders wisely determined that an emergency provision was necessary to prevent lengthy vacancies in positions that cannot, in the interest of the citizens, remain vacant for extended periods.

Thus, Article 2, Section 2, clause 3 was inserted, stating, “The President shall have Power to fill up all Vacancies that may happen during the Recess of the Senate, by granting Commissions which shall expire at the End of their next Session.”

Suppose the United States is at war with a foreign adversary. Congress has formally declared a holiday recess and will be absent from Washington for weeks. At this time, if the defense secretary dies of a heart attack, our national security interests are compromised by an emergency vacancy at the head of the nation’s military.

The president should not be forced to wait until Congress returns to fill the defense secretary position with the traditional confirmation process, so a recess appointment permits the president to staff his Cabinet with necessary individuals temporarily while still preserving the Senate’s constitutional check of advice and consent. That is why Article 2, Section 2, clause 3 makes the recess appointment temporary — it expires “at the End of their next Session.”

Such emergencies are what recess appointments are intended for, not for matters of expediency.

The need for a recess appointment was significantly more imperative when one considers the nation’s history. When senators traveled by horseback to their home states, a recess appointment provision was necessary because it could be quite a while before the Senate could return from recess. Justice Antonin Scalia said the recess appointment has become an anachronism; senators travel by plane and have many other options at their disposal.

The Supreme Court has stated time and again that the Senate’s power to advise and consent is a “critical structural safeguard of the constitutional scheme,” Edmond v. United States, 520 U.S. 651, 659 (1997), and noted that the founders viewed it as “an excellent check upon a spirit of favoritism in the President” and a guard against “the appointment of unfit characters from family connection, from personal attachment, or from a view to popularity.” The Federalist No. 76, p. 457 (C. Rossiter ed. 1961) (A. Hamilton).

The Supreme Court has also noted that the structure of the appointments clause ensures quality appointments and officers are made. The appointments clause of Article 2 is more than a matter of “etiquette or protocol,” Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1, 128-131 (1976). “By vesting the President with the exclusive power to select the principal (noninferior) officers of the United States, the Appointments Clause prevents congressional encroachment upon the Executive and Judicial Branches.” Edmond, 520 U.S. at 659. “This disposition was also designed to assure a higher quality of appointments: The Framers anticipated that the President would be less vulnerable to interest-group pressure and personal favoritism than would a collective body.”

The court has also noted that the reasons for the advice and consent of the Senate is to protect both the president and the Senate — and, most importantly, the citizens of the republic. Absent the appointments clause, the blame could fall squarely on one person (or the Senate if it refused to consent).

Hamilton said in Federalist 77: “The blame of a bad nomination would fall upon the president singly and absolutely. The censure of rejecting a good one would lie entirely at the door of the senate; aggravated by the consideration of their having counteracted the good intentions of the executive. If an ill appointment should be made, the executive for nominating, and the senate for approving, would participate, though in different degrees, in the opprobrium and disgrace.”

The constitutional process of presidential appointment and Senate confirmation, however, can take time because the president may not promptly settle on a nominee to fill an office; the Senate may be unable or unwilling to speedily confirm the nominee once submitted. That is not a flaw in the system but is its functional design.

Recess appointments have a clear and specific purpose outlined in the Constitution. Not for expediency or for personal satisfaction, the Senate confirmation process is far superior to ignoring checks and balances.

Outside of their intended purpose, recess appointments are an affront to the Constitution of our limited government. It would be wise if President-elect Donald Trump allowed the Republican-majority Senate to promptly confirm his picks as the Constitution prescribes. The Senate would also be wise to confirm his nominees with all deliberate speed so his administration can hit the ground running.

• Daniel Schmid is a constitutional attorney and the associate vice president of legal affairs with Liberty Counsel, an international nonprofit, litigation, education and policy organization dedicated to advancing religious freedom, the sanctity of life and the family.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.