Worried parents have been keen to send their children to school with cellphones ever since the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and mass shootings ushered in the new millennium. Now, public officials complain that students are using smartphones more for cyberbullying, video games and pornography than for talking or texting with Mom.

New York Gov. Kathy Hochul, a Democrat, has become the latest public official to crack down on what she considers to be digital distractions from learning. Kicking off a statewide “listening tour,” she promised this month to introduce a bill to ban smartphones in schools.

“The status quo is not working for our children in particular,” Ms. Hochul said during an appearance at Guilderland High School, a short drive from the state Capitol in Albany. “And I want to make sure we continue to incorporate community feedback.”

Liz Repking of Cyber Safety Consulting, an Illinois-based company that works with schools to develop internet safety policies, said she sees no legitimate reason for K-8 students to have smartphones at school and little cause for high school students to have the devices.

“My experience in the past school year is that the disruption to learning in the classroom is becoming insurmountable, especially for the most dedicated teachers,” Ms. Repking said.

She endorsed a growing school trend of locking personal phones in pouches that can be accessed only before school, after dismissal or in emergencies requiring parental contact.

“Without question, the most effective approach is a complete ban on phones from entry to exit to the school,” Ms. Repking said. “This also means that students will not have access during passing periods, lunch and recess.”

Public and private schools nationwide started distributing digital tablets and laptops to students in the late 2000s, and many allowed personal phones in classes for educational purposes such as video projects. The trend peaked from 2020 to 2022 as schools switched to hybrid and virtual learning with livestream classes during pandemic lockdowns.

Over the past year, several states and large urban school districts have abruptly reversed course. They cited a surge of student anxiety, depression and misbehavior, including drug dealing and posting embarrassing videos of teachers online. Test scores have declined, they said, and faculty are too overwhelmed to police cellphone use.

Most schools still allow approved tablets or laptops for some lessons, especially in math and sciences.

The move to purge cellphones has gained support across the political spectrum:

• The Los Angeles Unified School District announced last month that by January, all social media apps and cellphones will be off-limits to students. The district said students are sitting alone during lunch glued to their phones rather than socializing.

• New York City Public Schools, the nation’s largest district with roughly 1 million students, has promised a policy that may involve confiscating phones at the door each morning.

• Florida enacted the first statewide law restricting student cellphones in public schools last year. Indiana and Ohio did the same this year.

• Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin, a Republican, issued an executive order this month that directs public school systems to restrict nonacademic cellphone use by January.

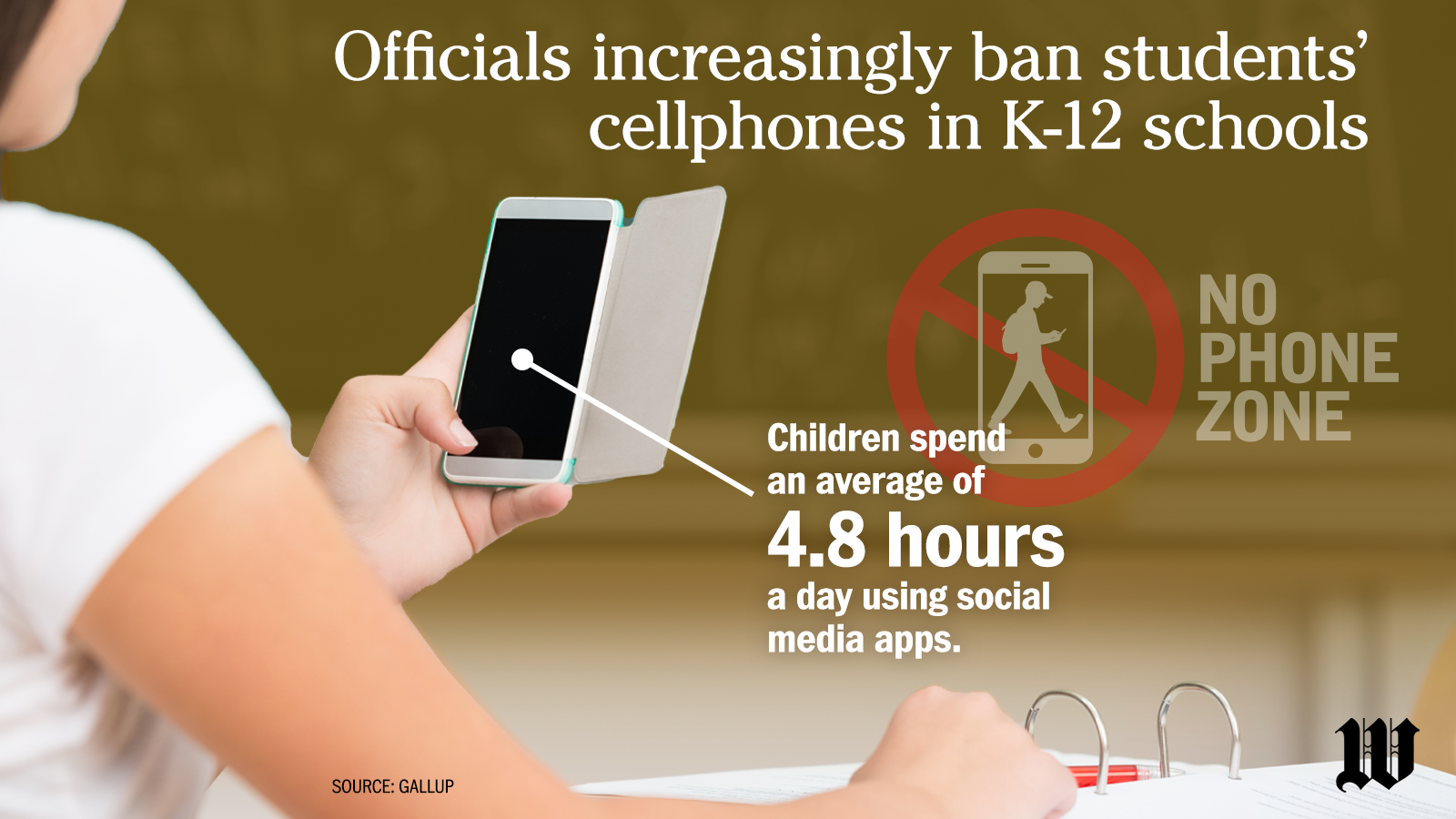

Todd Reid, assistant superintendent for strategic communications at the Virginia Department of Education, noted data showing that suicide and depression rates have soared since 2010 and that children spend an average of 4.8 hours a day using social media apps.

He said many jurisdictions in the commonwealth have already banned social media. Rural Louisa County implemented restrictions in 2008.

“Parents, family members, teachers and even the kids can see that something is wrong,” Mr. Reid said in an email. “They see how children have withdrawn from spending time with friends to spending ever-increasing time with phones.”

Stewart D. Roberson, a former public middle and high school principal in Fredericksburg, said “time will tell” how well parents adapt to the forthcoming rules.

“There will be an adjustment period for everyone,” said Mr. Roberson, an education professor at the University of Virginia. “In response to the parental concerns about their children having access to their phones in emergency situations, the utilization of personal pouches is the current best practice being adopted by some districts.”

Public officials said addiction to digital screens is driving a “youth mental health crisis” since pandemic restrictions shuttered K-12 schools in March 2020.

In an op-ed in June, Surgeon General Vivek Murthy asked Congress to slap a tobacco-style warning label on social media.

In a May 23 advisory, Dr. Murthy pointed to “ample indicators that social media can also pose a risk of harm to the mental health and well-being of children and adolescents.”

Mitchell Prinstein, chief science officer at the American Psychological Association, said students need freedom from digital distractions to recover from pandemic learning losses. He noted that several European nations, including Britain and Italy, forbid personal phones in schools.

“Science demonstrates that internet surfing during class time leads to lower grades, not just among the kid who is surfing, but for the kids sitting behind them, too,” Mr. Prinstein said in an email. “It is important for parents to know that ‘starter-phones’ like flip-phones still exist and are a great way to stay in touch with kids without giving them a distracting device that could affect their academic performance.”

Nevertheless, he said, no evidence shows that smartphone use between classes either helps or hurts students.

The Department of Education has no position on mobile devices in schools.

“This is a state and local issue, not a federal one,” an Education Department spokesperson said in an email.

In January, the Education Department reported that 76% of public schools banned nonacademic cellular use during school hours in the 2021-2022 school year, the latest available data.

Reports suggest the number has grown.

In Ohio, a bill that Gov. Mike DeWine, a Republican, signed in May bans cellphones “at all times” during school hours.

“It is about time, though that time should have been years ago,” said Ray Guarendi, a Catholic media personality and family psychologist in Canton, Ohio. “No question, access to the whole world in the palm of a child’s hand does much more damage than just limiting academic performance.”

In Los Angeles, city officials will let each campus decide how to implement the ban on personal phones, including the option of placing them in a locker or pouch during school hours.

Laura DeCook, the California-based founder of mental health education company LDC Wellbeing, said she “strongly supports” such policies.

“Unmonitored phones can easily distract students, hindering their focus and learning,” said Ms. DeCook, who leads mental health workshops for families. “Additionally, they create opportunities for cheating, eroding the value of genuine academic effort.”

Doctors say digital screens pose the most significant risk to younger children, who can develop social media addictions as early as the toddler years.

A study published this month in JAMA Network Open found that children ages 18 to 32 months who played a popular digital app game interacted less with their parents and were less responsive to behavioral requests than those who played with a real toy.

Dr. Dimitri Christakis, a pediatrician and the study’s lead author, said the findings highlight the need for children to interact face-to-face with one another “in real time and space” to ensure healthy social and emotional development.

“Schools need to provide a hotline for parents to be able to reach their children during school hours in case of emergency,” said Dr. Christakis, an investigator and professor at the Seattle Children’s Research Institute, affiliated with Seattle Children’s Hospital and the public University of Washington. “This is not a new approach; it’s what most of us grew up with, and it worked just fine.”

David Griffith, an official at the National Association of Elementary School Principals, said the emergence of smartwatches poses additional challenges for schools.

“As technology evolves, schools must continually adapt to ensure focused and effective learning environments while preparing students for a digital world,” Mr. Griffith said.

Some parental rights groups say cellphones have advantages.

Sheri Few, president of the conservative U.S. Parents Involved in Education, said smartphones have helped some families hold schools accountable for political bias in classrooms.

“We [wonder] if this is actually an attempt to hide bad behavior by teachers and administrators, which has increasingly become apparent via student recordings,” Ms. Few said. “It is a shame, but some educators’ behavior justifies our concerns.”

• Sean Salai can be reached at ssalai@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.