OPINION:

Before boarding a recent flight out of San Diego, I played a game of sorts: How many people would glance at the bold-lettered signs warning passengers that the jet bridge and airplane they were about to board may expose them to chemicals known to the State of California to cause cancer, birth defects and other reproductive harm?

You’d think such an ominous warning would elicit some disdain, or at least convince passengers to quickly make their way through the jet bridge and into their seat. But expediency be damned, not a single passenger glanced up at the warning, let alone altered his behavior because of it.

Today’s society is so full of warnings without context that we’ve tuned out what it means for something to be dangerous in the first place. In large part, the culture of “warn first, ask questions later” was bred out of the wild success of the U.S. government’s anti-smoking campaigns.

When the surgeon general identified cigarette smoking as a cause of lung and throat cancer in 1964, the action spurred health warnings on cigarette packages and a broad public education campaign highlighting the dangers of tobacco.

Today, the Comprehensive Smoking Education Act of 1984 requires cigarette manufacturers to display one of four rotating health warnings about chemicals present in cigarette smoke, chronic diseases associated with smoking, its risk to pregnancy, and the benefits of quitting.

The campaign played a significant role in convincing nearly half of adult smokers alive today to snuff out their cigarettes for good. Importantly, it also gave activists a blueprint for what methods work to take down some of the most powerful industries at the time. Suddenly, lifestyle choices that contribute to obesity, diabetes, and cancer more broadly, began to be tackled under the same guidebook.

The strategy led to warnings of breast and colon cancer on alcohol in Canada, raising the specter of obesity, diabetes, and tooth decay on juice and soda labels in San Francisco, and the deluge of warnings we see covering seemingly innocuous products every day.

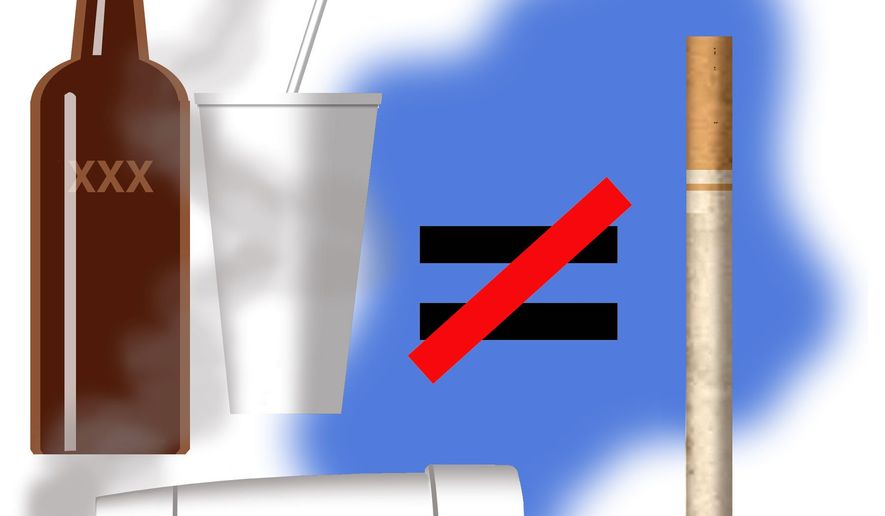

But what the explosion of warnings fail to mention is risk. When it comes to cigarette smoking, no amount of exposure is beneficial. Some studies show that the risk of lung cancer increases by an additional 8 percent every year that a smoker continues their habit. Treating products with far less substantial risk as one and the same dilutes this message.

Consider the jet bridge warnings. The first tells passengers that alcohol served on the plane may increase their cancer risk, and warns pregnant passengers that it may also cause birth defects. Just below it was a second sign carrying the same warning for jet fuel fumes. Neither contains the context necessary for passengers to make an informed decision.

It’s no secret that an excess of alcohol is tied to liver disease, including cancer, but it takes a lifetime of heavy drinking to get there. An airplane-sized serving of beer, wine, or spirits cannot contribute the same risk.

Jet fuel contains known carcinogens, but the most extensive studies of Air Force personnel who are regularly exposed to the fumes don’t show higher cancer rates than the general population.

Among the general public, even the top 10 percent of frequent flyers take just 5 or more trips per year. That equates to a cumulative total of perhaps 10 to 15 minutes of exposure to fumes. If the basis of this cancer tie is shaky in the first place, scaling it down to the risk level present in the general public makes the probability of harm negligible.

But in California, warnings like these are required by law under Proposition 65. Any business with 10 or more employees is required to warn their customers of the chemical dangers lurking inside their products and places of business, even if those chemicals pose no risk. Since so many businesses service California’s 39 million residents, the excess of warnings has bled out beyond the Golden State’s borders.

Just last week, a federal judge blocked California’s plan to require a similar warning on Roundup weed killer products, a move which could have also resulted in warnings on all the food products that had ever been grown with Roundup.

Imagine — your cholesterol-free, gluten-free, all-natural soy milk branded by a warning that it causes cancer. As manufacturers already affected by Prop 65 have experienced, it is cost-ineffective to sort out which products are headed for California and need a warning sticker, so the labels would have ended up on everything.

When U.S. District Judge William Shubb issued his ruling on the compulsory glyphosate warning, he noted, “the required warning for glyphosate does not appear to be factually accurate and uncontroversial because it conveys the message that glyphosate’s carcinogenicity is an undisputed fact, when almost all other regulators have concluded that there is insufficient evidence that it causes cancer.” In short, calling glyphosate a carcinogen amounts to compelled lying.

The judge’s invocation of compelled speech may have a substantial impact on our crisis of over warning. If a product must first be non-controversially proven to cause cancer before a warning can be placed on it, we may soon see fewer meaningless warnings overall.

His decision wasn’t a judicial anomaly either. In Canada, cancer warnings on alcohol met an abrupt end once liquor companies threatened to sue for defamation. Unlike cigarettes, alcohol can be incorporated into a healthy diet. In fact, if any scientific finding qualifies as “non-controversial,” it’s that moderate alcohol consumption contributes to a reduction in heart disease and stroke.

And in San Francisco, a federal appeals court blocked the implementation of the city’s sweetened beverage warnings. The court cited national health authorities like Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), who agree that added sugars are safe in limited quantities, while the warning conveyed the falsehood that “sugar-sweetened beverages contribute to [poor] health conditions regardless of the quantity consumed or other lifestyle choices.”

But each of these instances shares a common thread: A company or trade association which got out in front of the compulsory warnings and brought (or threatened to bring) their conviction to court. Sodas are not cigarettes. Alcohol is not cigarettes. And by god, cereal, granola bars, and Ben and Jerry’s ice cream are not cigarettes.

When businesses roll over to the unfounded demands of activists, we end up in a world so burdened by needless warnings that the ones which do matter aren’t being paid attention to. In the long run, we’re all worse off for their cowardice.

• Richard Berman is the president of Berman and Company, a public relations firm in Washington, D.C.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.